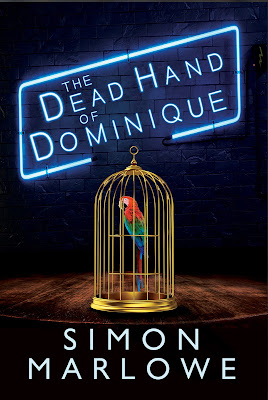

Interview with Simon Marlowe, author of The Dead Hand of Dominique

Today it gives the Indie Crime Scene great pleasure to interview Simon Marlowe, author of The Dead Hand of Dominique.

Your crime novel, The Dead Hand of Dominique, came out in November 2021. Tell us something about the novel: who is Dominique and what is her hand?

The novel is narrated by a young career villain

Steven Mason, who lives on a run-down housing estate along the fringes of

London and Essex. He is tasked by his gangland boss (nicknamed Grandad) to

track down his missing girlfriend Dominique. However, Steven knows things are

not going to be simple, when he discovers a frozen hand in Mickey Finn's old

fridge. Steven then travels up to London with his mate Anthony (a junkie artist

who Grandad uses to launder money), to begin the search for Dominique. As Steven

speaks to people connected with Dominique, he begins to uncover a plot which is

about revenge, money, power and control. And it all centres on the dead hand,

what is on the dead hand, and if it is Dominique’s.

Hopefully, the narrative will grip the reader, with the intention that you will want to know how all the pieces fit together – which you will only really know once you get to the end. But it is also underpinned thematically by two key political and social issues: the increasing commodification of people’s needs and wants as inequality accelerates, and contradictory conscious - the theory that people have conflicting ideas and are not homogenous in their thinking. I will leave that up to the reader to identify in the complex mix of characters, most of whom are hell bent on finding what lies at the end of a rainbow.

You mention that the novel will appeal to fans of Guy Ritchie and Fargo. What made you choose those examples? What do they mean to you?

I like to use references which are familiar to people, and I believe film and TV has far more of a reach than literature: it is relatable and people can get quickly drawn in i.e., first impressions at an interview give you a good chance of getting the job! Also, Dead Hand is written in a style that could translate quite easily into film. So, choosing Guy Ritchie as a reference point reflects the characters and environment of the novel - and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels would be a good indication of the type of ride the reader will go on. As for Fargo, I thought the darkly comic criminality, character, and plot of the film and TV series was something I have sought to emulate in Dead Hand (at least I can say I tried!).

Your protagonist, Steven Mason, is described as “a young career villain”. What is a career villain and what makes Steven tick?

A career villain is someone who has crossed the Rubicon (through choice, fate or other), to live a life of crime, where their needs and wants are met by working full time on acquiring and accumulating through illegal means. It is, in essence, their profession, just like a banker.

There are two things that motivate Steven: survival, and the aspiration of a different way of living.

You have said “people are not one or other, criminal or non-criminal, rather people transition in and out of such a way of life”. What does this mean to you in the context of the novel and more generally?

There is nothing fixed about who and what you are, and this is something the central character Steven is thinking about. He dreams of escaping from the path he is on, from the families which have shown him the professional life of earning a living as a criminal – but it just doesn’t appeal to him to be doing this forever. There are also characters in the novel who do criminal things but are not as professionalised as Steven. Their motivations are either altruistic, short term, or driven by impulse or emotion, rather than planned and premeditated.

This leads on to my own broader perspective on criminals and crime. I think the reality for most people is not like a grand narrative, between good and evil, between criminal and non-criminal. For most individuals it is nuanced, layered and complicated.

And from a societal and economic perspective, crime is an industry. It is a significant slice of any economy, whilst legal systems perpetuate the illusion that crime does not pay, when in fact, it does pay handsomely, but for the few and not the many. Only a few get rick legally and only a few get rich illegally.

For me, crime, in as wide a sense as possible, is committed by the most powerful, the boastful, the arrogant, the nation state, the standing army, the uniformed and non-uniformed oppressors. There is a difference between the crime of the oppressed and the crime of the oppressor. I am not an advocate of crime, both can be devastating for victims, but there is a difference between the criminalising of people and the criminality of business and political leaders, which is becoming more and more brazen, and less and less accountable – to the point where it is almost normalised.

Often crime novels involve a sleuth who solves crimes, with an antagonist who is usually a criminal. What made you decide to take a different approach?

I all ways have several ideas either in my head or sketched out, and I had been desperately trying to find a way to write about crime and kept hitting a brick wall with Private Investigator characters that just didn’t have enough life about them. I then thought: what if I flipped the thing on its head? What if the investigator is the criminal, what if the crook is like a PI, a gangster Poirot? That would be different, and yet still contain the key elements of a mystery which needed to be solved.

|

| Walton on the Naze Sea Defence B&W Aug 2022 by Simon Marlowe |

My novels reveal things about myself, but are heavily disguised, so nobody really knows if such and such a thing ever happened! All I can say: fact is stranger than fiction.

As to where I come from. Well, Essex is one of six counties which surround London and provide workers for the global city and financial hub. It is where I was born and bred, in a sleepy dormitory town, which if you are from the States, would be like Newark is to New York (I once spent the night in Newark when my plane was delayed because of a faulty cabin door: we had the choice of parachutes or a night in the hotel, so I opted for the latter).

Anyway, when I was growing up, most kids just wanted to leave, because it was a boring soulless suburban hole. So, you only had to get on the train and in 40 minutes and you were in London (South London being south of the river Thames). And the great thing about a global city like London is it has a large chunk of the world in a very small space. In fact, I’ve probably met more people from all over the world, from every social class, than I have from any travelling.

Eventually though, I got tired of it all (plus I was homeless), and I knew there was a roof back at the suburban ranch. And that’s when my view of Essex changed. It has a reputation for ‘chavs’, which is snobbery for looking down on people, and/or poor working class kids chasing celebrity status (i.e., the reality show The Only Way is Essex). But with anything, there is a lot to unpick, and there is truth and reality to Essex (the clichés are true, but so are the things that people do not hear). There are parts of Essex which have a diaspora from the East End of London, reaching all the way along the Thames, and up to seaside towns which are either quaint, retro or desolate. There is also a patchwork of small villages which have olde worlde thatch cottages and black timbers propping up buildings full of subsidence. But the best part of Essex is out towards the coast, the estuaries, the 400 plus islands, the marshes and the comforting bleakness of the flat farmland, ditches and hedges. It has a melancholy which you can see in films like The Woman in Black, or the TV series The Third Day with Jude Law (both filmed on Osea Island).

Somehow, I now like it. With all its history of rebellion, revolt and modern-day conformity, there is a truth about Essex which I hope will be told rather than laughed at and mocked.

How much did your early career and life experience lead you to become a writer?

I have had two phases in my life when I have tried to be an author. The first time I tried was not a success. I was a teenager, and the best way to sum it up was like a Billy Elliot experience, although I aspired to be an author and not a ballet dancer. Then I wandered aimlessly as working-class young man struggling to find my place in the world. I am very conscious of my class status, and it wasn’t until my early thirties that I began to understand what this meant for someone like me.

The breakthrough, in my torrid life, was when a Lecturer said the most important thing to me: ‘You are an intellectual.’ It sent my head spinning, because up to that day I was a like a pin ball in a pin ball machine, a blind Tommy, battered and bruised and spinning like an out of control spinning top. It was a long haul from that point on, and there have been ups and downs. I am not a ‘professional academic’, but I feel secure in my thinking, and find fiction the platform I need to say what I want to say, in the way I want to say it, unimpeded by intellectual niceties.

Therefore, this is my second phase, when in my forties I re-connected with that deeply held passion to become an author. Twelve years later, I have my second novel via an independent publisher. And I thrive on that independence; it gives me the freedom that a traditional publishing route would never give me. And I can see independent authors and independent publishers are the new disruptors. It is just going to be a hard nut to crack.

Your first full length novel, Zombie Park is described as “an intense and darkly comic drama, set in a dysfunctional psychiatric hospital during the social and economic turmoil of the 1980s.” What made you choose that decade as a setting?

There were two reasons for setting the novel in the 1980s, one practical and the other thematic. Firstly, it is based on my experiences of training to be a psychiatric nurse in the mid-1980s, so for authenticity and an easier transfer of experience into drama, I did not have to change anything. Therefore, a fair portion of it is semi-autobiographical, which anyone who reads it may find a bit jaw-dropping! Plus, rule of thumb for a first novel is to write from experience, although it did not make the writing journey any easier because it took seven years to write.

Secondly, Zombie Park is still fiction, and conforms to those parameters, structure and form. Therefore, in the process of writing I had to search for abstraction, elevating the novel above raw description and into a literary product. That meant understanding the importance of that time, the significance of the 1980s as a key decade between the old and the new, the economic and political breakdowns, as we moved from one way of doing things to the new age of globalisation. In a small way, my experience in a psychiatric institution had parallels with these changes, as individualism triumphed over the social contract.

Is there an analogy between the “dysfunctional psychiatric hospital” and 1980s Britain?

The simple answer is yes! The zombies in Zombie Park are the psychiatric patients who have been dulled into submission by the liquid cosh and the rigours of institutionalisation. Then, along comes community care (also known as "Care in the Community"!), which in principle seeks to liberate this oppressed population from the poor practices of Victorian Psychiatric Wards. But when discharged long-term patients are faced with an uncaring society, Care in the Community serves only one purpose: financial savings and ex-patients struggling with the vagaries of vulnerability in a predatory society.

In Britain, in the mid-1980s, there was a break with the old economic and political model. There are various terms used in economics to describe this: structural adjustment, monetarism, or Hayek’s Chicago School of thought. Politically, in Britain, it become known as Thatcherism, in the US Reaganism). Here, the threat to society was Trade Unions, who had apparently become all powerful, although in hindsight we now know they had already been beaten before the miners tried one last desperate attempt to preserve a living. But the analogy is that in Britain, the old order broke down to usher in the new age of capitalism, of rampant individualism, the fragmentation and cutbacks of welfare systems, and the loss of social cohesion.

And so, to move the analogy one step further, as the old geopolitical order of the Cold War system collapsed, and the Soviet Union fell apart, it was seen that capitalism (and a particular kind of capitalism) had triumphed.

But does anybody now really feel they have found greater freedom since the 1980s, or only a different type of oppression? As bad as the psychiatric hospital was, it had one benefit, sanctuary, which was taken away from those who needed to be helped, to be protected from a society that did not understand them. And did people who had lived under authoritarian communism find freedom through capitalism, or were they also in for a shock when they realised that nobody cared? And do we, in the West, and the developing countries, feel the benefits of this freedom? Or are we increasingly left to fight on our own against the collective might of a narrower and narrower body of the rich and powerful?

Just a thought…

In your author bio it says you are a “literary writer, [who] often uses the thriller genre to tell stories which combine realism with a blend of the surreal.” What does that mean to you?

One of the hardest things when you have created something is then having to describe what it is you have done, how and why you did it. However, you also know as an artist (in the generic sense of the word) that if you can’t describe or articulate what it is you’ve done, this will cast some doubt on your credibility as an artist. After all, who is going to listen to somebody who says they don’t know what they are doing having painted the Sistine Chapel (although you could argue that the art speaks for itself)? Not that am trying to compare myself to Michelangelo, but merely trying to define my approach as an author, how I lean towards the thriller as a genre, how I like to create a sense of realism which can be disrupted at any moment by the slightly bizarre.

In fact, I quietly resent the genre because it feels like a pigeonhole, a cul-de-sac, a marketing tool rather than adding to the creative mix. But I also accept it is a necessary evil, the bedrock of the scaffolding for the evolving narrative and plot line. Graham Greene struggled with defining his books, labelling them ‘entertainments’ and literary. I believe towards the end of his life he became reconciled that they were all one, and not one or the other. I am just trying to define what I do as an author, so it sounds as if I know what I am talking about, but this might not all ways be the case!

|

| There might be a way in Marlowe 2022 by Simon Marlowe |

I have a rather small portfolio of work because 95% of the time I have free is spent writing. If I am lucky enough to have the means to become a full-time author the ideal would be to write in the morning and paint in the afternoon. I find the two disciplines complimentary (i.e., writing and artwork) although I am confident as an author and less so regarding my artwork.

However, I try to take a thematic approach to both canvas and photography, representing as best I can the geometric forms which make up our world, either in the urban or in nature. It is what I tend to see a lot of, whether it is staring out of a train at the overhead lines as they move up and down, or the clash between buildings and concrete up against fluid natural forms.

Are there any writers of crime fiction - or other fiction - who you particularly enjoy?

I must confess I am not a big reader of crime fiction but would count Patricia Highsmith or Elmore Leonard as favourites. I have probably been far more influenced in terms of writing crime fiction by American ‘dirty kitchen’ literature such as Herbert Selby Jr, William Burroughs or Bukowski. However, I was drawn to my own interpretation of crime thrillers by going back to English writers such as Eric Ambler and Patrick Hamilton. Their pre and post war novels did two things: a compelling narrative underpinned with a quiet radicalism; they reflected the big issues of their time without screaming in your face with overly virtuous didacticism.

But if I wanted to put my feet up and bury my head in a book it would have to be something by Philip K Dick. He was trapped within his genre, science fiction, wrote serious literature that never got published, and yet wrote the most compelling, imaginative stories which make all the minding numbing drivel which is churned out today look like children’ stories in comparison. I have tried to imitate and had my fingers burned. I will be back to at some point to emulate the master, probably with some imitation of Vonnegut along the way. But that is some way off. For now, it is crime fiction!

What writers influenced you when you were starting out?

The first authors that inspired me were DH Lawrence and Ernest Hemingway. I then got my teeth into James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. That pulled me into European literature, existentialism, and I devoured all that I could find that was in translation - until someone pointed out to me that a translation is not the same as reading it in the original language. Of course, I was never going to rapidly learn French, German or Italian, and many years later realised that this was an example of a put-down! I still retain a fondness for translations and would recommend Celine’s Journey to the end of the night, a great example of saying things without inhibition, and turning it into something profound and meaningful.

You have mentioned Guy Ritchie - are there any other directors whose work you admire?

There are many, as I am a big fan of film and the new streaming services which have adopted a lot of the high value film production values (although I appreciate fans of pure film can see it as a problem).

So, just to mention a few directors: the Coen Brothers; Quentin Tarantino; Takeshi Kitano; Ken Loach.

And I do especially like South Korean film, which to me is the most imaginative and innovative now: Park Chan-wook; Bong Joon-ho; Sang-ho Yeon.

I am currently working on a sequel to Dead Hand, which picks up where the narrator Steven leaves off at the end of the first book. All things being equal, this should be ready for publication next year, followed by a final Steven Mason novel which is sketched and should follow the year after. So, the Dead Hand is the first in a trilogy of crime fiction, thematically drawing on political and social issues, with a good helping of the darkly comic, perhaps increasing in darkness, but also hopefully keeping the reader wanting to know what happens in the end – and we all want to know what happens in the end?!

Amazon | Cranthorpe Miller | Waterstone's

About Simon Marlowe:

I grew up in Essex and then spent most of my formative years living in South London before finally settling backdown in mid-Essex with my family. Like some people my age, I’ve done far too many things to list them. All I can say is that throughout my life I applied the principle to experience as much as possible, to try things out, never wanting to be in a position where I regretted not having had a go at something. It means I have a rather eclectic mix of experiences and professions, which provide a vast quagmire of material and reference points to draw on.

Eventually, I became an author, probably because I always was one, it has just taken a very long time to learn how to be one. What held me back is another story, one of those books that authors have in their back pockets and know one day they must finally get down to write.

As for my latest novel, I like to think of it as the product of the creative process. I am not sure what kind of qualifications you need to write about crime and criminals, other than those who I have come across are people just like you and me. Just as there are in all walks of life people who are different, who behave well, sincerely, or act badly, bully or are cruel. There is not a criminal gene, although a positive or negative choice is required to get involved in crime or to behave criminally. The point is that criminals have the same level of nuance and complexity as the rest of us. Also, people are not one or other, criminal or non-criminal, rather people transition in and out of such a way of life. Criminality though is based on exploitation of others, it thrives on moral ambivalence, and is harsh and unrelenting in its distorted reflection of the legitimate environment that most of us live in. It is an upside-down world which commodifies more rapaciously than any other way of life; it is a world within a world, and often a branch which people grab to survive the choppy waters they are drowning in.

90% of my creativity is spent on writing but I have been slowly building a small artwork portfolio of geometric artworks, whilst also developing a portfolio of photography.

Comments

Post a Comment