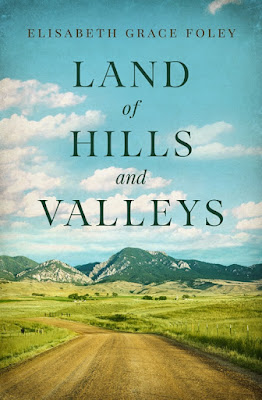

Interview with Elisabeth Grace Foley, author of Land of Hills and Valleys

Today it gives the Indie Crime Scene great pleasure to interview Elisabeth Grace Foley, author of Land of Hills and Valleys.

Tell us about Lands of Hills and Valleys, your most recent novel.

When Lena Campbell inherits her grandfather’s Wyoming ranch, she discovers that an unsolved mystery goes with it—his murder. As she adapts to her new life, which includes falling in love, the nagging question of who really killed her grandfather stays with her. But when fresh evidence breaks the case open again, it strikes closer to home than she could have imagined. She’ll have to find out the truth about Garth McKay’s death if she is ever to lay to rest her frightening doubts about those closest to her.

What made you choose Wyoming as a setting and how important is the history of the place to your book?

While I’m interested

in the history of all parts of the American West, the beautiful landscape of

the Wyoming and Montana area personally appeals to me most strongly, and I

think that’s why I most enjoy writing stories set there. In this particular

book, which is set in the 1930s, the focus is mostly on the story’s present

day, but some Wyoming history does play a small role in the backstory.

The novel begins with your heroine inheriting a ranch from the grandfather she never knew. The word “ranch” is deeply evocative of the myth of the old West, even to people who grew up in Europe. What does it mean to you?

You know, that’s

true: it’s really a very distinctly American term and image. I personally think

the term “mythical” has been way over-used in connection with the Old West. Though

there is definitely a set of clichés associated with the West that have been

distorted into historical inaccuracy by books and movies, the word “myth” implies

something that didn’t really exist, and over-emphasizing it obscures the fact

that there is a root of reality behind the legends. Stagecoach hold-ups, range

wars, conflicts between cattlemen and settlers—even though they may look very

different in the movies (sometimes absurdly so), those things really did

happen, and sometimes the reality is even more interesting than the fiction!

And the working ranch is perhaps the most important of all those realities.

Although there were plenty of other things taking place in the West besides

ranching, the cattle industry was what really drove settlement of the land and

shaped its culture.

The novel is set in the 1930s - what is the significance of the historical setting?

I began the first draft of Land of Hills and Valleys as a teenager, largely under the influence of old “B” Western movies such as those starring Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. They were set in a quirky no-man’s-land of their own 1930s and 40's mixed with guns and horses and shootouts alongside automobiles and radios—great fun, but without the slightest pretensions to historical accuracy! In subsequent drafts and revisions I had to strip out traces of the B-Western influence, but I found that an authentic 1930s setting suited the story well and I stuck with it. I’ve always been interested in the Great Depression era too, and have experimented with a few short stories set in that period. (I don’t mind admitting that I leaned heavily on Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird to get through the courtroom scene in Land of Hills and Valleys.)

The blurb recommends the novel to fans of mystery and romantic suspense in the style of Mary Stewart and Phyllis A. Whitney - what do those authors mean to you?

I discovered Mary Stewart eight years ago when I read Nine Coaches Waiting (still my favorite of her books!), and she quickly became one of my favorite authors and biggest literary influences. Her romantic-suspense novels typically feature a very relatable and down-to-earth protagonist caught up in a bit of mystery with a spice of danger, set against the backdrop of a gorgeously written setting and featuring a light touch of humor and romance. I had struggled for several years trying to write Land of Hills and Valleys more as a traditional murder mystery, and then I had my big breakthrough when I decide to experiment with writing it in first-person narration strongly influenced by Stewart’s style. While it is a murder mystery, it’s not as formally structured as your typical whodunit with an official sleuth hunting down clues—re-framing it to tell the story through Lena’s eyes and focusing on how the revelations in the murder case affect her worked perfectly.

Phyllis A. Whitney is

sometimes referred to as an American equivalent of Mary Stewart, but she tended

more toward the Gothic and melodramatic: the sinister mansion full of deep dark

family secrets! To me the two authors are pretty distinct but I think there’s a

significant amount of crossover with readers who enjoy both.

Are you first and foremost a writer of historical fiction or a crime writer?

I call myself a

historical fiction writer who often writes mysteries. Everything I write is

historical fiction, but though I very frequently include a mystery element, it’s

not present in every single story—I’ve also written comedy, fairytale

retellings, and straight historical/Western fiction that doesn’t belong to a

particular subgenre.

Your short novel Left-Hand Kelly was nominated for the Western Fictioneers’ Peacemaker Award in 2015, and your work has appeared online at Western fiction site Rope and Wire. Tell us more about this and its significance to you as a writer.

The Peacemaker nomination was definitely a big confidence-booster, in a time when I was still finding my feet and figuring things out as a writer. My Western short stories tend to be “straight” Western without a mystery element, written largely for my own pleasure since they’re not quite as marketable these days, and it’s great to have them published at a place like Rope and Wire, which puts them in front of readers and gives me an outlet when I feel like writing that sort of thing.

How does the Western setting lend itself to crime and mystery stories?

I remember writing in my journal years ago when I was wrestling with the plot of Land of Hills and Valleys, “If you get stuck with the plot of a Western mystery, add rustlers.”

Seriously, though, while you can certainly weave plots around distinctively Western crimes like rustling, horse-thieving, claim-jumping and so forth, one of the things I’ve been keen to do is demonstrate that the West is as good as any other historical era for setting mysteries that are strong on character development and relationships. You can play with classic whodunit tropes adapted to the setting—a locked-room murder in a frontier town, a travel mystery like Murder on the Orient Express on a stagecoach, a “country house” mystery with a variety of guests at the headquarters of a wealthy rancher—and craft suspense and explore human nature just the same as you could in the more popular Victorian or medieval historical-mystery settings. (And also, what I think some tend to overlook is that the heyday of the American West is a part of the Victorian and Edwardian eras in America.)

As a woman, what challenges does writing Westerns present, and how do you react to the legacy of writers such as Louis L’Amour?

I honestly worry far

less about fitting a mold or fulfilling expectations in a genre than I did when

I was younger. I used to worry that if I followed my own tastes and style I

wouldn’t write Westerns hard-bitten enough for male readers; I worried that I wouldn’t

be able to attract the interest of the large number of readers (especially

women) who had no interest in Westerns because they viewed them merely as

shoot’em up action stories. These days I’m much more comfortable with simply writing

the kind of stories I like to write and trusting them to connect with readers

who like the same things. Part of getting to this point was realizing that I

didn’t need to try and hang onto the coattails of big-name authors. L’Amour is

definitely a pillar of the Western genre, but he did rely heavily on gunfighter

tropes; and there have been so many imitators of L’Amour, and imitators of the

imitators, that the paperback western has in some ways become a parody of

itself. Then, too, I did a lot of musing a few years back on something I

noticed about the Western genre in the 20th century, particularly on

film: even as far back as its Old Hollywood heyday, it had already morphed into

a vehicle for expressing contemporary ideas and attitudes through a framework

of popular Western plot devices—and that’s continued up to the present day. The

fact that the genre in its commercial form has changed so much has actually

really freed me from the burden of trying to live up to anyone else’s legacy

and to write according to my own vision of what a Western is.

Tell us about your series the Mrs Meade Mysteries. Who is Mrs Meade and how does she become an amateur sleuth?

Mrs. Meade is a middle-aged widow living in a small town in Colorado around the turn of the 20th century—a setting I found fascinating because of its combination of Old West frontier with the more modern innovations of the prosperous Edwardian era. It seemed like an ideal setting for a mystery series because of the variety of interesting people and activities you could find there—Colorado was home to ranching, mining, and railroads, as well as being a popular health resort (plus gorgeous mountain scenery!). Mrs. Meade doesn’t really have an origin story, but her qualifications as an amateur sleuth are mainly a shrewd understanding of human nature and an eye for important details—and as one character in the series remarks, a tendency to be just across the hall whenever puzzling problems befall one of her friends!

Are you planning to write any more books in the series?

At this point let’s say I would like to, though I don’t have any immediate plans for new titles. I do still have a couple of sketches for Mrs. Meade plots tucked away in a notebook, which could possibly be written one day. We’ll see.

What are the pleasures and challenges of writing historical novels?

They say that writers get to live many different lives through their characters, and one of the chief pleasures of writing historical fiction is getting to vicariously spend time in different eras that fascinate you! The biggest challenge, I think, is being faithful to the time period—not just avoiding factual goofs, but trying to reproduce the spirit and atmosphere of the times, and make your characters think and behave in a way that rings true.

What do you like to read when you are not writing and researching?

My reading tastes are

reflected pretty well in what I like to write! Classics, mysteries, vintage

books in general, history, theology, poetry.

How did you come to be interested in the West? Was it the place where you grew up, or somewhere you encountered on film and in books?

I’ve never travelled

beyond the northeastern U.S. where I was born and grew up, so it was definitely

something I discovered through film and books. I grew up watching old Western

movies and TV shows, and looking back now, I can see that among the books I

read as I child I always liked stories of American pioneers and settlers, from

the Little House on the Prairie books

to the Kirsten series of the American Girl books and more. (I was also

completely horse-crazy, so I think the abundant presence of horses in Westerns

was a big draw too.) Then as a teenager I discovered classic Western fiction

from authors like Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour, and gradually became more and

more interested in the history of the West as a whole.

What are you working on next, and what are your plans?

My current project is actually something a bit different from anything I’ve written so far—a Ruritanian novel! For those not familiar with the term, it comes from the imaginary country of Ruritania in Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda, and it’s a subgenre of books set in fictional European countries and dealing mostly in romance, adventure, and court intrigue. Much as I like working with real historical detail, it’s fun to freewheel with something totally of my own invention for a change (but it does have an Edwardian-era timeframe, though the people and places are imaginary).

I do definitely have

plans for more novels in my usual style—I currently have ideas sketched out for

three books that are all Western and all mysteries, though pretty different

from each other.

What do you do to relax and are there any crime or historical novelists you love?

I love spending time out of doors, going for long walks and doing a bit of gardening. I enjoy listening to classical music and bluegrass, crocheting, and watching German football (soccer, for my fellow-Americans). My favorite type of crime fiction is definitely the classic Golden Age murder mystery, and I would say at this point my top authors in the genre are Josephine Tey, Ellis Peters, and Dorothy Sayers.

Amazon | Kindle | Kobo | Smashwords | Nook

About Elisabeth Grace Foley:

Elisabeth Grace Foley has been an insatiable reader and eager history buff ever since she learned to read, has been scribbling stories ever since she learned to write, and now combines those loves in writing historical fiction. She has been nominated for the Western Fictioneers’ Peacemaker Award, and her work has appeared online at Rope and Wire and The Western Online. When not reading or writing, she enjoys spending time outdoors, music, crocheting, and watching sports and old movies. She lives in upstate New York with her family and the world’s best German Shepherd. Visit her online at www.elisabethgracefoley.com.

Wonderful interview! I really enjoyed all these insights into your process. This part really resonated with me:

ReplyDeleteThese days I’m much more comfortable with simply writing the kind of stories I like to write and trusting them to connect with readers who like the same things.

I think that's a HUGE part of why I didn't start writing westerns until I was in my mid-30s. I finally was comfortable with writing what I loved instead of what I thought people wanted to read, and it turns out there's an audience out there for westerns still, after all :-) But I needed that comfort with my own skin, and that confidence in my own abilities without the carrot of outside approbation.

I love what you have to say about writing letting you experience a different time period a little bit, too. That's one of my favorite things about reading historical fiction!